They say it’s not what you earn, it’s what you keep. There’s some truth to that in terms of growing net worth. But how do you figure out how much is enough?

Over the years, I’ve explored best practices to managing and growing lifetime finances. In graduate school, I became interested in investing and wrote a monthly financial newsletter for several years (see here for some samples). Once I started working, I realized the importance of early income to my long-term financial outlook.

My more recent focus is how to pay attention to finances at all, when most of my time and energy is devoted to career and family. While tracking the Arc of Our Careers, how can we also track the Arc of Our Finances to make sure that we’re on target with where we want to be?

The best strategy I’ve used for projecting my life finances on a single spreadsheet. Here’s how it works…

EconDad Link: Family Financial Projection Spreadsheet

“I think you messed up the formulas, Dad.”

Projecting Your Life Finances

I’m a regular reader of personal finance writers. I’ve read dozens of books (all-time favorites are The Millionaire Next Door and Rich Dad, Poor Dad), and I actively follow several writers online (especially Ramit Sethi, Financial Samurai, Mr. Money Mustache, Physician on FIRE).

My favorite personal finance article of all time is “The Shockingly Simple Math Behind Early Retirement.” Here’s the punchline and key chart:

“Well, I have a surprise for you. It turns out that when it boils right down to it, your time to reach retirement depends on only one factor: Your savings rate, as a percentage of your take-home pay.”

“If you save a reasonable percentage of your take-home pay, like 50%, and live on the remaining 50%, you’ll be Ready to Rock (aka “financially independent”) in a reasonable number of years – about 16 according to this chart and a more detailed spreadsheet* I just made for myself to re-create the equation that generated the graph.”

Source: The Shockingly Simple Math Behind Early Retirement

There’s a direct inverse relationship between your savings rate and your years to retirement. At 70%, it’s only 8.5 years. At 50%, it’s 17 years. At 20%, it’s 37 years. Naturally, it’s more nuanced if you dig deeper. But if you’re saving only 5-10% of your income, I can’t think of any concept — other than seeing 50 to 70 years until retirement — for why that’s not enough.

The best strategy I’ve come up with, that balances awareness, clarity, understanding, long-term thinking, and financial psychology is tracking my life finances in a single spreadsheet. I started tracking in 2011 and have been doing it for 7 years now. It’s been my best tool for feeling in control, staying on track, keeping my emotions in check, and making good financial decisions.

Tool: Family Financial Projection Spreadsheet

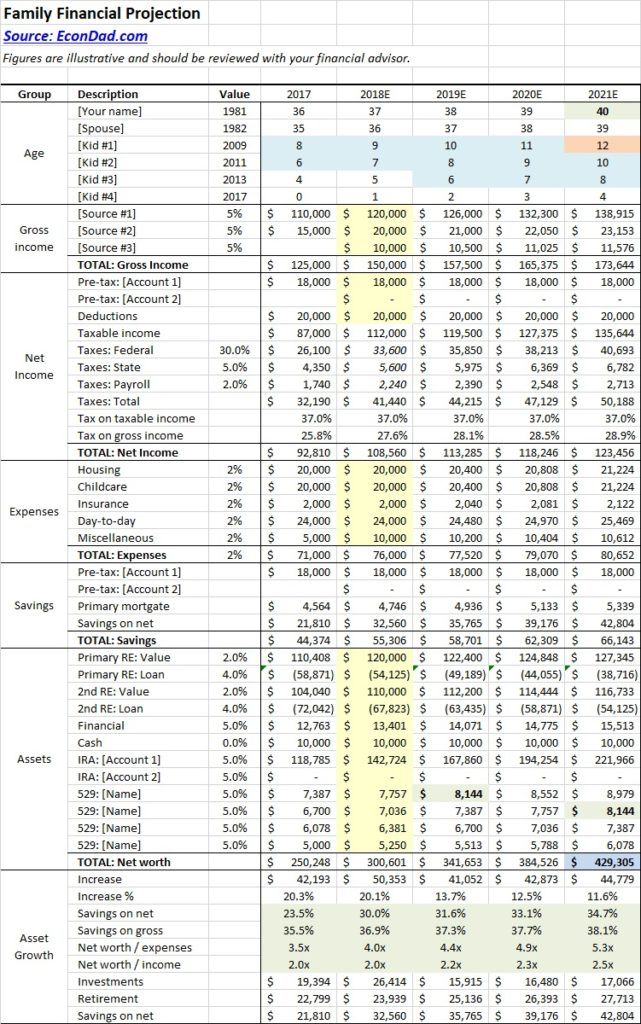

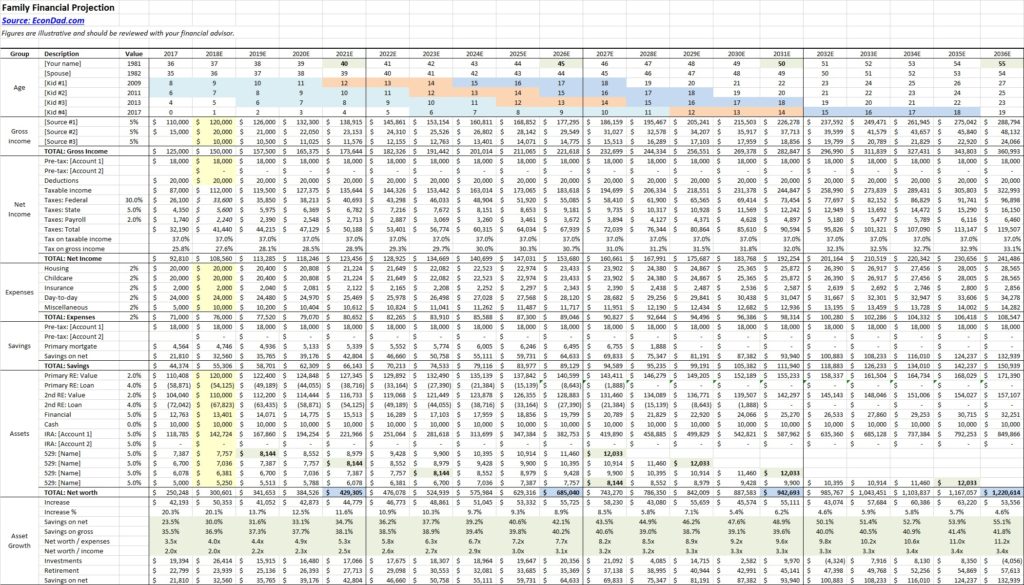

Here’s a deep dive into how I actually track my life finances. I’ve scrubbed the numbers to be illustrative (sorry, I’m not sharing *that* level of detail), but the following spreadsheet is a true representation of what I actually track. Here’s the link, with screenshots and descriptions below:

EconDad Link: Family Financial Projection Spreadsheet

An economist projecting the family finances

I know what you’re thinking: “Wow, DeForest is so cool!” Just kidding, that’s what I was thinking. You were probably thinking: “Wow, what a nerd!” And, truthfully, it is kind of nerdy. There are tools that can help you track in a more automated way (like Personal Capital), but I prefer the micromanagement and awareness that comes from doing my own calculations.

Here are the key benefits of this kind of tracking:

- Awareness. The only way to know what’s happening under the hood is to track over time. I like tracking on an multi-year timescale, because you can look back over 5-10 years and see how things have progressed (or not progressed).

- Understanding. Having a spreadsheet shows you exactly how much you’ve earned, paid in taxes, spent, saved, and grew your investments. It helps you identify the key levers that will make a difference in your long-term financial outcome looking forward.

- Clarity. Tracking your finances helps you define your goals and know whether you’re hitting your savings targets. Am I saving enough? What is “enough”? If you don’t even know what your targets are, how are you going to improve your approach?

- Long-term thinking. This one is key: projecting your life finances helps you identify whether or not your current projected path is where you want to be. How do you know if you’ll end up in the right place if you aren’t projecting where you’re headed?

- Financial psychology. It takes mental soundness to stay on track. It’s easy to try to “keep up with the Joneses” and be jealous of others, so you’re better off defining a projected path and sticking with it.

I’m a big fan of the writers in the FIRE community (Financial Independence, Retired Early), because they’re savvy, motivated, and have demonstrated success in achieving financial independence. I’ve learned so much from them. At the same time, their patterns do not reflect how most people operate — most of us aren’t trying to maximize savings at the expense of enjoying life. We find our work to be meaningful (even if stressful at times), and we like spending money rather than being ruthlessly frugal. Sure, the FIRE community is inspiring, at times, but extreme frugality not realistic or reflective of what I observe for most people.

I’ve personally found peace in a middle ground that works for me: Spend less than you earn, make sure your projected path looks good, and then don’t worry about it so much.

I personally don’t get much satisfaction from eeking out a few more percentage points on my savings rate, say, from 20% to 22.5%. Clipping coupons drives me bananas. I’m much more comfortable saying, “Great, I’m in the 20% to 40% savings range, and I’m good with how that plays out over time.” Then, I don’t have to feel guilty for spending so much on childcare or if we decide to visit Fenway to root for the Red Sox (or maybe the Dodgers?) in the World Series.

A contrarian at heart

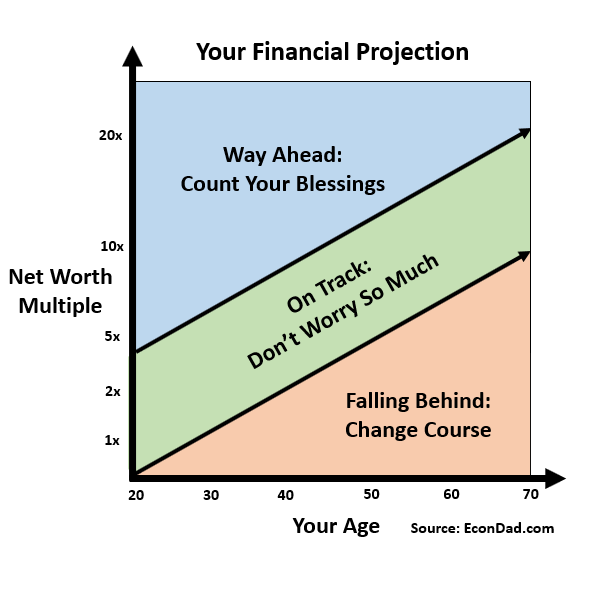

The following chart shows my Goldilocks mentality: Don’t be too hot or too cold. Instead, aim for “just right” and stop worrying:Let’s dive in further.

Deep Dive by Category

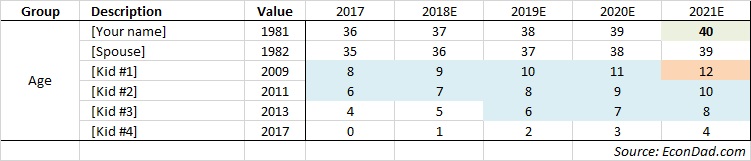

1. Age. Start by projecting your family ages over time. So many financial milestones depend on age, especially for kids and college. When I say to my wife, “Wow, who would have thought we would end up with four kids?” She often says back, “Come on — you’ve had that fourth kid on the family spreadsheet for 5 years now!” Point taken.

Here’s what it looks like for us (true ages). For the kids, I’ve shaded the cells for elementary school, middle school, and high school. I’ve identified age 18 as the point where we give them a strong handshake, a big check, and send on their way to spread their wings at college.

As an aside, just mapping out your kids’ ages gives you some perspective of how little time we have with our families at home. Kind of like Tim Urban’s “Your Life in Weeks.” Plotting out their ages may remind you to hug a little more and yell a little less.

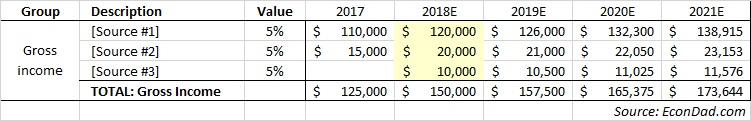

2. Gross Income. Next, plot out how much you’ve made and how much you expect to make in terms of top-line income. This is revenue coming in the door, and the only way to really grow your family projection at the beginning is to increase this top-line number.

If both you and your spouse work, plot that on several lines. Separate your sources of income so you can see which are most important: For example, record your trust fund income separately from your jet rental income (ha! just kidding). Record the numbers as they were historically, and then plug in your estimated amount for this year and growth rate going forward.

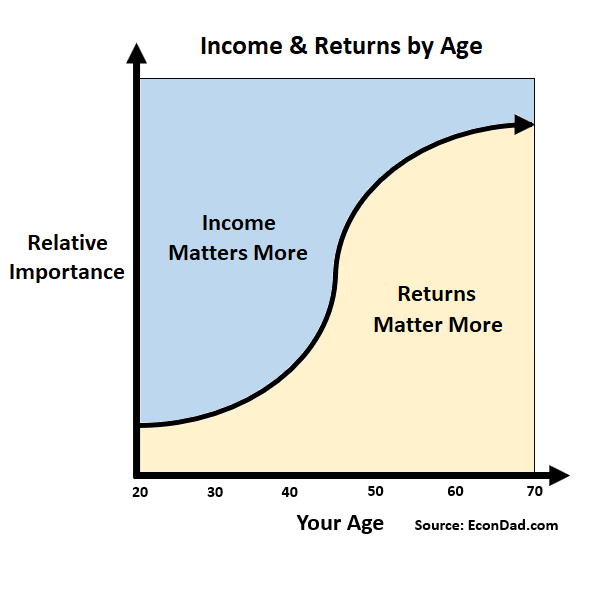

It took me a while — longer than it should have — to realize that long-term financial success, especially early on, depends more on high early income than on investment returns. For example, if I’ve saved up $50,000, it makes very little difference whether I get a 6% return ($3,000) or a 10% return ($5,000). That $2,000 difference is way less than any difference I get by finding a higher paying job or getting a raise.

Early on, you’re much better focusing on career and income growth. After you’ve saved enough, investment income and labor income start to become equally important. Eventually, in later life, investment returns should outweigh additional income received from working.

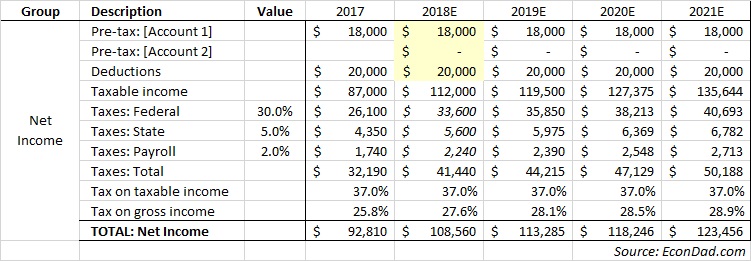

3. Net Income. Net income refers to available money after your visit from the Tax Man. Even my son gets steamed up about taxes: “What? The government takes 40% of your income? That’s not fair!” “We all have to contribute to the broader society, bud.” “I’m never paying taxes.” “If you feel that way, I know someone you can ask for advice.“

Calculate the net income by deducting your pre-tax accounts (like your 401k) and subtract your taxes paid. That’s how much you have left to spend versus save. If you don’t know your effective tax rate (the total percentage of gross income you paid in taxes), you should find out.

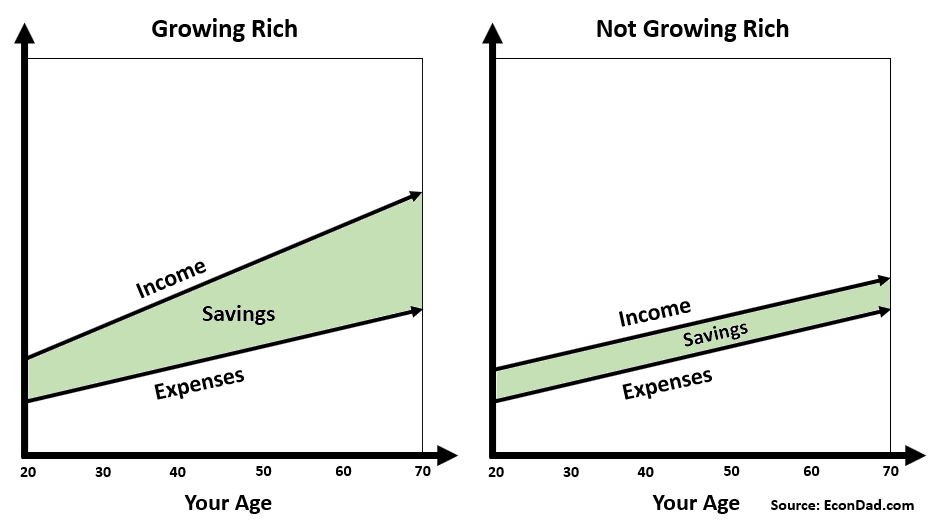

4. Expenses. Here’s where things get interesting. I’m not a big fan of tracking expenses down to the millimeter. As Ramit Sethi likes to say, “Nobody ever got rich by not spending $3 on daily lattes.” And he’s right. You don’t get rich by micromanaging spending (although I’ve seen some ultra-frugal FIRE writers have some success with this), you grow rich by having your income pull away from your expenses.

We put our family spending into five broad categories: (1) Housing, (2) Childcare (includes school and summer camp expenses), (3) Insurance, (4) Day-to-Day, and (5) Miscellaneous. They first three are pretty self-explanatory, yet the last two are pretty broad and all-encompassing: “Day-to-Day” represents any spending that occurs regularly (food, clothing, phone bill, Internet) and “Miscellaneous” represents any big pictures that are infrequent (travel, new car, etc.).

Our true figures for childcare expenses are eye-poppingly high (at least to me), but they’re necessary for supporting four kids and two career-oriented parents. We’re Protecting Our Most Valuable Assets by staying happy, healthy, and productive, so, for us, childcare is a critical pillar of family spending that actually yields a good return on investment. As my grandfather liked to say about spending money on the kids: “Hey, it’s cheaper than drug rehab.”

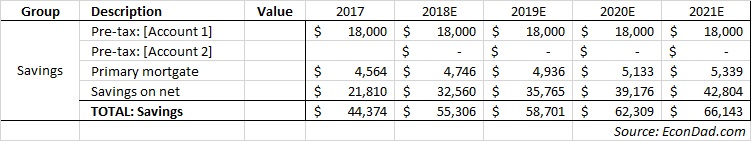

5. Savings. Here’s where the fruits of our labor convert to money in the bank. Savings equals net income after taxes minus spending. Easy peezy, right? But, you should at least know where your primary buckets of savings come from, including pre-tax accounts (from above), pay down of your primary mortgage (yes, I’m counting that), and savings on net income, which is your take home pay after taxes minus your spending.

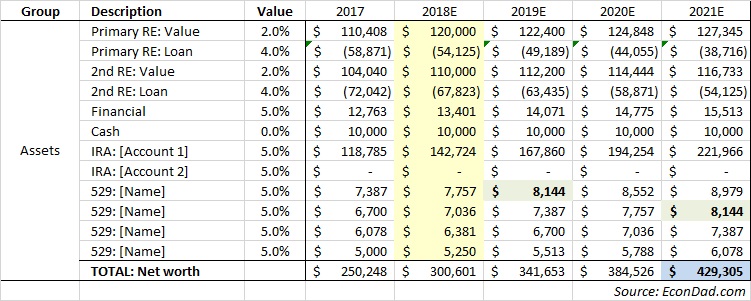

6. Assets. Here’s where our saving accumulate. You can list any assets in terms of real estate, investments, cash, IRA, or even the kids 529 savings accounts. This represents your total net worth, which you can track over time.

Tracking your assets in this way gives great insight into the relative benefits of each asset class. You can see the power of a rising real estate market, where your mortgage size is fixed but your home price increases, even if no more than the rate of inflation. You can see how much you’re giving up by safer assets versus riskier assets. You can see how diversified you are across your various assets.

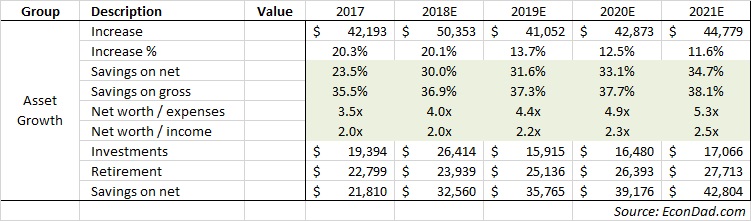

7. Asset Growth. Lastly, I track how much our total assets grew each year. As they like to say (the proverbial “they”) : “If you’re not growing, then you’re dying.” Same with assets.

I calculate several key metrics that I compare across years:

- Increase in net worth (%). How much did my net worth go up over the past year, from savings + investing?

- Savings on net income (%). How much did we save of our take-home pay, after taxes? We’ve been targeting 25-50%, but it’s been lower in recent years with more kids.

- Savings on gross income (%). How much did we save of our top-line income, including mortgage paydown and pre-tax accounts? We’ve been targeting 20-35%, but it’s been higher and lower than that too.

- Net worth / expenses. Ratio of net worth to expenses. If you’re going to retire early, you’d better grow this metric to 10x or 20x (see Financial Samurai’s Net Worth Targets by Age, Income, Experience for the best discussion of this).

- Net worth / income. Ratio of net worth to income. Similar to expenses, but tracking the multiplier to replicate your income rather than your expenses.

- Investments, Retirement, Savings. A bottom line breakdown of how much net worth grew because of investment growth vs retirement growth vs savings. If you don’t know the inputs, you’ll never reach the desired output.

Putting It All Together

So there you have it! I maintain the family financial spreadsheet usually monthly but at minimum once a quarter. But I keep the calculations as annual amounts. One benefit is to zoom out on the whole spreadsheet on my 32″ computer monitor to literally (correct usage) see the big picture of my family financial projection. Here’s what it looks like over a 5-year period:

Still with me? Here’s what it looks like over a 20-year period:

“See what I mean? Super simple.”

Final Thoughts

Monitoring my family finances in this way has provided with important perspective and economic insights that I would otherwise have missed. Here are some of the biggest ones:

- Income vs Investing. Income matters more than investing in early years. Investing matters more than income in later years. See the above figure on this.

- Saving “enough.” As long as you’re saving “enough”, don’t stress so much even if you’re spending a lot. The trick is figuring out what “enough” is. Try to find your “enough” so that you’ll be content if your projection plays out like you plan it.

- Short run: Cut spending. Cutting spending is more important in the short run, so you get more near-term mileage from reducing spending than increasing income.

- Long run: Grow income. Growing income is more important in the long run, so you get more long-term mileage from increasing income than reducing spending.

- How to get rich. The most straightforward way to get rich is to have your income far exceed your spending for many years in a row. So your options are basically: (1) pursue a high-income career path, (2) start a business, (3) spend frugally, or (4) give up on being rich (which is also okay!). Remember that you can still live a Rich Life even if you aren’t a Rich Person.

Readers: Do you track your life finances? How? Any tips on improving my approach?

Related articles:

Comment from a friend: “My own Econ Dad/Husband could get some tips for improving his spreadsheets 🤓 He has three weddings for our daughters in our expense column 😂😩”

Ha! That’s great. I have mostly sons (3 boys, 1 girl), I’m not sure what is the latest etiquette on who pays who for weddings. Glad to hear he’s got it all mapped out!! 😆😆😀

I’ve rarely seen so much usable information in such a concentrated format. This is one article I’ll be [1] reading more than once and [2] sharing with my three sons. Thanks!

I think spreadsheets are very personal but i have to say I downloaded yours and learn a fair bit how to improve my personal own.

I downloaded this and can’t stop tweaking it! I have run at least 5 sceneries for retiring and then watching the money come out of the assets to provide income. I created a new row that takes the total savings and invests it as after tax money. I just can’t stop, it is so addictive. It would be great to see a follow up blog about withdrawal rates or which accounts to use for income. Fabulous job, so much fun, more addictive then video games.

I have a question on updating. so are the columns the end of the year or the beginning? Like at the end of this year which column do add the current numbers? My guess would be 2018.

Great! So glad you like it! I’ve found it to be very helpful in my own planning.

For your question, I usually think of the current year as an end-of-year expectation — where will we be at the end of the calendar year? That way, I can incorporate expected earnings / savings / returns for that year. Sometimes, I’ll add in an extra column for “current” in between last year and the current year to give more detail, but I usually find the end-of-year analysis to be sufficient.

Thanks for reading and good luck!!

Hi there. How can you assume your assets are going to grow at the fixed rate you have plugged into column “C”? This appears to be a projection only, not reality. Am I missing something here?

Halyard

I think of that as an assumption going forward. You can’t use “actual” figures for the projection since they haven’t happened yet. If you want to tweak your expectations you can change the parameter. Thanks for reading and good luck!!

Interesting Post! thanks!

How do I read the graph that has your net wort multiple and your age on it? What is the multiple? 10x, 5x what? Thank you for all the great information!

You can use one of two net worth multiples:

1. Net worth / Income

2. Net worth / Expenses

If you use a 4% withdrawal rate, which is considered the “safe” withdrawal rate by many in the FIRE community, you need a 25x net worth divided by expenses multiple to retire forever. I think you need to get up to 1x to 2x to start feeling good and 5x to 10x to start feeling free. Net worth divided by expenses is probably more meaningful since it defines what you need to retire. Hope this helps and thanks for reading!

Love it!

Do you think this can be converted to a Google Sheet without issue? Any conditional formatting or other incompatibilities?

Hi! I’m not sure whether it will work, but the formulas aren’t complicated (nothing conditional or complex in there, just interest rate math). I’d love to hear how it goes if you give it a try. Thanks for reading!

Maybe I’m looking at this wrong, but it seems there’s double Pre-tax account counting for the “TOTAL: Savings” summation. That sections sums Pre-tax accounts (K33, K34), mortgage, and “Savings on net” (K36). But Pre-tax account values are already implicitly included in the “Savings on net” (K36) as it uses “TOTAL: Net Income” (K26) which does not subtract out Pre-tax accounts from K16 & K17.

I see that K16 & K17 are subtracted out to calculate Taxable income (K19) but K19 is not used in later downstream calculations

Hoping I’m wrong.

Good catch! I think you are right. I’ve fixed the worksheet here and in the link above: https://econdad.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/EconDad-Tools-Family-Financial-Projection.xlsx

The wealthy don’t bother with all this silliness while some unfortunate folks have no choice but to work until they can’t and then struggle with Social Security until they die.

For the rest of us spreadsheets like this can be really helpful. Will we have enough? Income changes year to year with jobs ending, social security and (sometimes) pensions starting. When can I quit working? How long should I wait to collect Social Security.

Econodad I appreciate your work on this. Thank you.

You bet! Glad you liked it. You’re right that the extreme rich and poor don’t need this kind of analysis, but for those of us in between, it can be useful…!