Here’s the situation: Your child isn’t listening. He’s disobeying, he’s hitting his sister, he’s screaming and acting like a little monster. You warn him, and no response. You threaten to take away his favorite toy, and no response. You put him in a time out, and he’s at it again five minutes later.

So you raise the stakes: “No more screen time…” “No allowance this week…!” “You’re grounded for a month…!!” “I’m not paying for college…!!!!” You keep ratcheting up the stakes, but nothing seems to work.

Here’s the question: Why not raise it to the next level, or to an extreme level? If you really want to deter behavior, why not threaten to kick him out of the house or cut off the ear of his favorite stuffed animal? These are exaggerations, of course, but they relate to a real principle of discipline and punishment: if you want to deter behavior, you can impose increasingly strict penalties in order to stop or prevent that behavior. So why not keep going to something extreme? Let’s explore this a bit more…

“Hey kid, stop doing that, would ya?”

“Hey kid, stop doing that, would ya?”

Source: IMDB for “Gladiator”

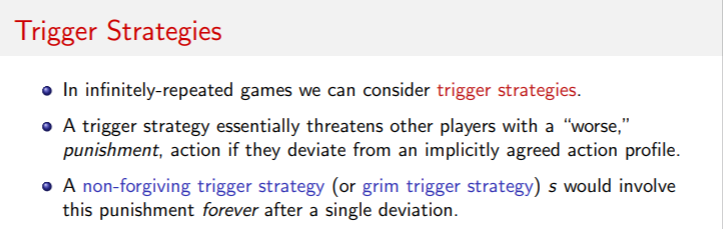

Grim Triggers and Extreme Penalties

In economics, there’s a concept in game theory called grim triggers. If you want to deter or prevent a behavior, you can commit to a penalty so severe and/or permanent that it’s called a non-forgiving trigger strategy or a grim trigger strategy. Here’s an excerpt from an MIT lecture on Game Theory with Engineering Applications:

Extreme penalties and trigger strategies may be “effective” in deterring the behavior. “If I’ll get kicked out of the house as a consequence, there’s no way I’m sneaking that extra cookie before bedtime.” The harsh penalty warrants strict adherence. You’d better pay attention, or Fluffy may lose an ear or two.

Parent contemplating a

Parent contemplating a

non-forgiving trigger strategy

Source: IMDB for “Gladiator”

Some actions may deserve harsh punishment — for example: the ancient principle of “An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.” That’s one rationale for the death penalty for murder, not only as a deterrent but also based on a sense of justice — whether or not you support it, you can see the logic.

That’s the rationale behind three strikes laws, where you get mandatory jail for life after the third offense. Effective, perhaps, but also harsh. That’s also why many parents use increasing penalties for children’s behavior. First time: warning. Second time: time out. Third time: lose your allowance. At times, you may even lose your cool and threaten to ground your child or lose his toys forever (not you, of course, asking for a friend).

Here’s the issue: While extreme penalties may be effective to some degree, they often don’t agree our notions of fairness and justice, because: (a) we all make mistakes, (b) the penalty is cruel regardless of what caused it, and (c) the penalty exceeds what we justly deserve for our wrong-doing. Harsh penalties may deter behavior, but they aren’t fair or just in light of the severity of the crime.

Kids are still learning right from wrong and figuring out acceptable behavior. We want them to learn low-penalty lessons at home so that they avoid big-penalty lessons in the outside world. “I’ll teach you not to hit your sister by giving you a time out, so that you won’t go to jail for hitting a colleague when you’re an adult.” Lighter penalties are desirable precisely because kids are learning. Even as old as teenagers, children don’t have fully developed prefrontal cortexes to help them make good decisions (my wife likes to call them “little non-human primates”).

So how to we properly calibrate discipline and penalties in this context?

What Are the Trade-Offs?

There are several key trade-offs and considerations when determining a proper penalty for misbehavior. For example…

Sometimes the deterrent effect is the most important consideration. If your child crosses the road without looking, you might impose a stronger punishment even if they didn’t cause any issues, because you so strongly want to deter that behavior in the future.

Sometimes justice and fairness considerations are most important. If a child makes a mess, we often punish by requiring that they fix the mess. “You made it, you clean it up. Or it’s going in the trash.” We want the penalty to be proportional to the infraction and to feel fair to the child, if you’re aiming for long-term compliance and acceptance.

Sometimes reputation considerations matter most. There’s a fun example from the book, Raising the Perfect Child Through Guilt and Manipulation (which is quite good, actually). The Mom (aka, book narrator and dictator of the house) found herself threatening to “kill the basketball” if the kids shot it over the hoop one more time. Naturally, the kids shot it over the hoop, like, 5 minutes later. So, while the punishment exceeded the crime from a justice perspective, Mom went out there with a knife and stabbed the basketball to death in order to preserve her reputation for enforcing the punishment. Sometimes these decisions are warranted, because they represent short-term sacrifices to justice and fairness in order to preserve long-term compliance with less severe penalties.

This is how your wife may look at

This is how your wife may look at

you if you “kill the basketball”

Source: IMDB for “Gladiator”

There are also notions of restorative justice to consider. How is the punishment going to help the offender (that little bugger) take responsibility for his or actions? To help him understand and internalize the harm caused, in an effort to heal the injured party and learn deeper lessons to minimize future transgressions.

Finally, there’s compassion itself, the idea that we love our children no matter what, even when they’re being little monsters. That doesn’t mean discipline goes out the window, but we do have to make sure that they know we love them, no matter what. There’s the infamous but sincere saying: “This is going to hurt me a lot more than it’s going to hurt you.”

How Do We Solve It?

Traditional parenting wisdom supports the three Cs: Clarity, Consistency, Consequences. For the last C, that means finding fair but effective penalties by balancing the above factors as best we can, to deter behavior but also impose consequences that are just and reasonable.

I’ve recently been reading Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, and I resonated with some ideas in the chapter titled, “Do not let your child do anything that makes you dislike them.” In it, he posits the idea that we discipline our children to make them socially acceptable to the world — if they’re doing something that you don’t like, other people are probably going to like it even less. Here’s one excerpt on an appropriate amount of discipline that resonated with me:

“Here’s a straightforward initial idea: rules should not be multiplied beyond necessity. Alternatively stated, bad laws drive out respect for good laws. This is the ethical – even legal – equivalent of Occam’s razor, the scientist’s conceptual guillotine, which states that the simplest possible hypothesis is preferable. So, don’t encumber children – or their disciplinarians – with too many rules. That path leads to frustration.

Limit the rules. Then, figure out what to do when when of them gets broken. A general, context-independent rule for punishment severity is hard to establish. However, a helpful norm has already been enshrined in English common law, one of the great products of Western civilization…

A single brilliantly practice principle can be used to generate all these incrementally more severe reactions: that of minimum necessary force. So now we have two general principles of discipline. The first: limit the rules. The second: use the least force necessary to enforce those rules.” (pp. 136-137, emphasis added)

Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos.

In other words: (1) limit the rules, and (2) use minimum necessary force. This is an approach I’ve been thinking about and working on at home lately. Easier said than done, but it resonates.

Is There Any Role for Physical Punishment?

One of my first posts on parenting was How To Win Any Negotiation With Your Child, an economic guide to negotiating with your kids, using concepts like BATNA (Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement) and strategies like Chris Voss’s “Using your late-night DJ voice.” I thought it was a fun and geeky way to point out negotiation strategies that parents might not otherwise think about.

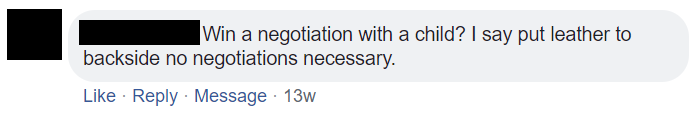

This was the first article where I overcame my anxiety and posted it on Facebook. Here’s the first comment I received:

Ugh, really? I followed up:

Fair enough. But I then proceeded a get a handful of comments from parents who still use physical punishment to deter behavior, for example:

It dawns on me that many parents still use physical punishment as the go-to extreme penalty. It may deter behavior, but it comes at a significant cost.

On some level, I get it. If you want to stop a behavior, impose a punishment severe enough to get your child’s attention. There’s a strong deterrent effect of physical punishment, precisely because it causes so much suffering. On the other hand, physical punishment has been declining for years. Most parents these days don’t spank, use a belt, and even seriously consider doing so in most circumstances. In addition to negative effects on the kids, it feels fundamentally unfair and unjust to impose physical punishment for a child that is developing and learning.

In implementing discipline, there’s a fundamental trade-off between effectiveness (getting your child to comply) and justice (designing penalties that are fair relative to the action). We can only hope to be as thoughtful as we can in handling this trade-off when raising our kids.

Final Thoughts

We’ve all been tempted, at times, to use extreme penalties to deter misbehavior. Have you ever felt the words slip out of your mouth, only to wish you hadn’t said them…? “You’re going to be grounded FOREVER!! Okay, not really…” As parents, we have to balance multiple considerations when deciding on appropriate penalties for undesirable behavior.

My wife and I have struggled with this over the years. In many cases, I think we’re too lenient. In some cases, I think we’ve been too harsh. We’ve had some success getting input from the kids on what the appropriate penalties should be — see this wonderful Ted Talk on Agile Parenting. Our favorite book overall is 1-2-3 Magic, focusing on clear warnings and consistent consequences, which has worked pretty well for us. We emphasize discussions of right and wrong, of course, and use positive rewards and reinforcement when we can. That’s all good stuff. But we also have certain behaviors that are not acceptable and need proper consequences in order to keep them in check.

Whatever your approach, think twice before you threaten extreme penalties. Because you don’t want to be stuck enforcing them when your kids break the rules.

Threatening extreme penalties may put you in a bind

Threatening extreme penalties may put you in a bind

Source: IMDB for “Gladiator”

I agree with your conclusion (and I’m reading Jordan Peterson too–he’s also popular with contemporary college students ).

Spanking wasn’t used with my kids (as I recall), but I did resort to “forceful holding.” My three sons may still remember what we called the “daddy death grip.” This was a firm hand-hold on the back of the neck as I walked them to their rooms for some infraction. The “daddy death grip” left no lasting mark and caused no noticeable [?] pain, but did convey *forceful energy* that demonstrated I had reached my limits.

My tone and demeanor in this context reflected overwhelming determination. There was no discussion or negotiation. “Resistance is futile.”

The “daddy death grip” was the next step if my verbal warnings that “the lion’s tail is swishing!” failed to produce results–which was rare.

I worked during my college summers as an orderly at a psychiatric facility for adolescents. Perfect training for being a parent! In that context we used what might be called “protective holding” –especially when patients were at risk of hurting themselves or others. “Protective holding” did not usually entail our overt verbalization of anger –that would typically do more harm than good–but it did convey what many adolescent patients needed and maybe wanted: *a sense that someone was taking charge and their lives were not spinning out of control.*

I like this. What you’re getting at is the need for a final or ultimate position that includes physical restraint. It’s your backstop as a Dad. When all else fails, use the *daddy death grip*, which is in line with the three Cs and is something you can commit to in advance.

Physical restraint is also good for a few other reasons: (a) it physically stops whatever misbehavior is occurring, (b) it de-escalates rather than escalates, (c) it keeps your own temper in check because restraining is the goal (i.e., minimal risk of using too much force), and (d) it hits on your last concept: Dad is here and keeping the world in order, even if you’re out of control.

All good thoughts. Thanks for sharing!!

A topic for the ages. I think credibility is particularly important. The moment you show them you are not credible, you can forget it. As for the Facebook comments you got, I’d like to talk to the kid of that first parent who claims that their kid didn’t battle much after a while, did what they were told, and that it ultimately turned to respect. I have a suspicion that the child’s side of that story may not be so smooth.

Agreed! Credibility and consistency are key. Sometimes you just have to “kill the basketball.” I, too, am suspicious of how smooth the other parents had it… 🙂