My most important life lesson from graduate school was in time series econometrics. Wait — what?? Yes, you read that right, folks.

My most important life lesson from graduate school was in time series econometrics. Wait — what?? Yes, you read that right, folks.

Here’s what I learned: Life is a random process, just like a statistical time series. There are areas of life within our control, and there is randomness out of our control. Life goes up, life goes down, much of it due to random chance in the world.

Our actions can influence the broader trend — based on how hard we work, what we value, and the choices we make. But much of life is left to chance.

Your life is a sequence of random events, one after another, that form your individual experience and achievement.

Setup

Let’s get technical (fair warning: this gets pretty geeky!). Here’s a basic time series process for understanding this:

- y(t) = y(t-1) × (1 + r (t) + e(t))

In other words, your position today, y(t) — whether measured in income, status, success, fulfillment, thriving, whatever — depends on your position yesterday, y(t-1), times a growth factor that includes a predictable component, r(t), and an unpreditable component, e(t). Let’s say r = 2% (your average growth rate), and e(t) = [-4% to 4%] (randomness of the growth rate). In other words, your growth progresses upwards an average of 2% per year, but might be as low as -2% or as high as +6% in any given year. In reality, the random swings are probably even greater.

You control the predictable portion (how hard you work, how much effort you put in) but you have no control over the unpredictable portion (the random things that affect us in life).

In one version of your life, you do everything right, you pass all your classes, graduate from college, get the great job, and life marches upward. In another version of your life, you try to do everything right but things fall apart — you get sick in your 20s, divorced in your 30s, depressed in your 40s, and so on. You might make the same choices but end up very differently.

I’ve found peace in recognizing the randomness in life. Life isn’t always fair or predictable, and it gets easier to accept and appreciate differences in life outcomes once we understand that.

Your Life Path

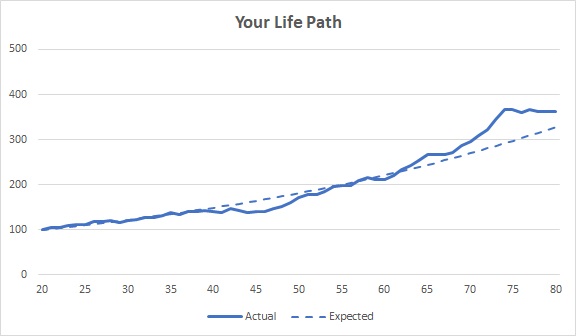

Think about how this might play out. Let’s plot your life path, from age 20 to 80. The x-axis represents your age. The y-axis represents whatever measure you care about — success, income, progress, satisfaction, whatever. The dotted line represents your expected path of 2% annual growth. The solid line represents your actual path, which sometimes moves up, sometimes moves down, but on the whole moves positively throughout your life:

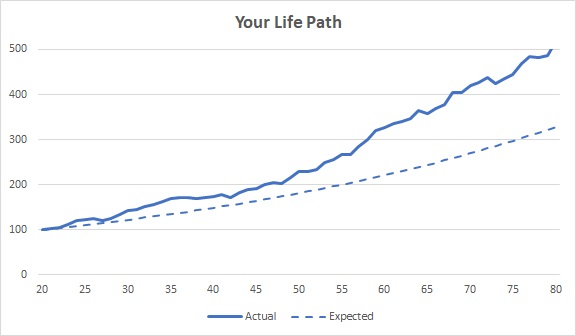

But what if luck is on your side? What if there are bank errors in your favor, success at your first start-up, and you marry the man or woman of your dreams? Then your life might look like this:

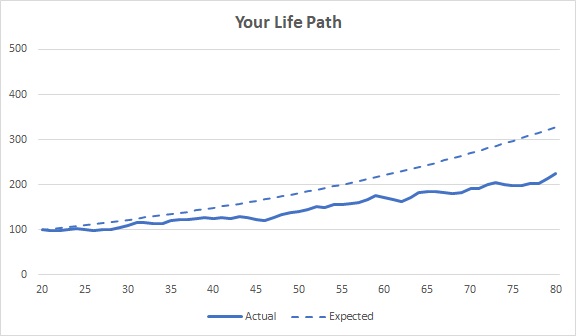

Let’s think about the opposite scenario, where you’re less lucky. Maybe you can’t quite get into the right college, or lose your job at a critical time, or you marry the wrong person. There are millions of things that can go wrong and throw you off course. Then your life might look like this:

But how do we know whether we’re above trend or below trend. How do we know whether our path was better or worse because of how hard we worked, or whether we just got lucky or unlucky? The different paths above are based on the same random process, not based on any changes in how hard you worked or the choices you made. We just… got lucky, or unlucky.

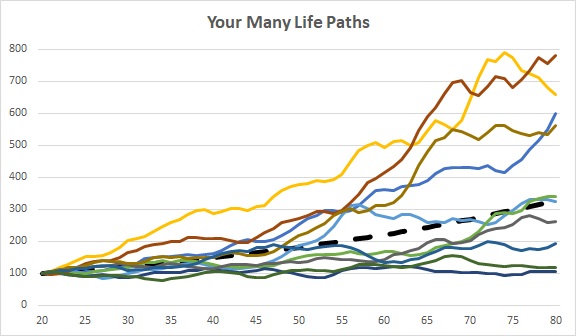

Your Many Life Paths

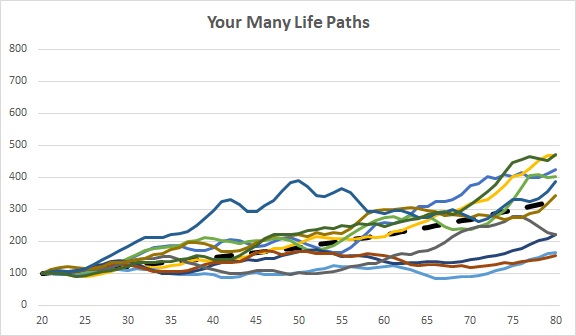

The truth is, there many life paths you could lead. Some are good. Some are bad. Most are in the middle. What if we plotted ten possible life paths all on the same chart:

These are all life paths that you could live, and you just happen to live one of them. Were you successful because you made good choices? Or were you just lucky? What if you’d moved across the country instead of staying in the state where you grew up, would your life be better or worse? What about if you majored in music instead of engineering, what then? There’s really no way to know how your life would have turned out in the alternative.

Watch what happens when we amp up the randomness. You might live very different lives — some of them on your yacht in Tahiti while others on your couch in New Jersey:

The point is that we cannot know for sure why our life turned out the way it did. Was it because of our choices? Or just randomness? Or even deeper, how much of our choices are actually in our control?

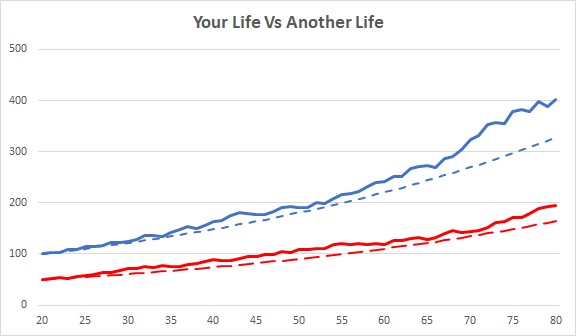

Comparing Life Paths

Thinking of your life in this way also raises questions about equity. What if your life turned out better than someone else’s, just because you were born to better parents or in a richer country. Consider the following chart, where you might have the exact same growth rate as someone else, but you’re better off because your starting point was higher:

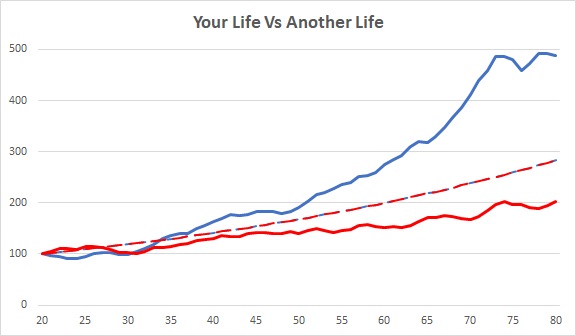

Or maybe you and your evil twin both started companies right after college. You had equal smarts, equal opportunities, equal chance of success. But your company thrived and his company floundered. You might compare your position to his and smugly think how great you are, but your success may have been due to being in the right place at the right time rather than any choices you made:

Same Expected Path, Different Actual Paths

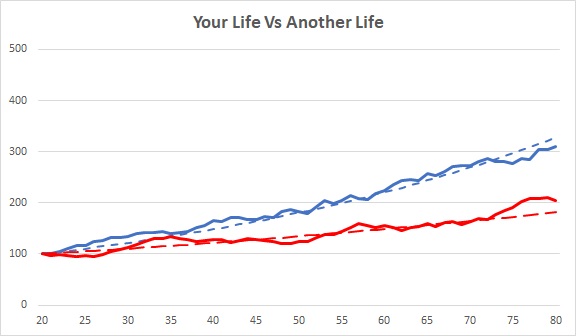

On the flip side, maybe you legitimately worked harder than your college roommate. While he slept at the beach, you worked your tail off. You got the good job, the good house, all the things you’ve wanted. Your life is better because you worked for it:

Working Harder Than The Next Guy

We might have some intuition or personal observations or even data on how much of success is due to choice versus chance. Important social questions depend on separating these factors — how much credit do we give to people who succeed, how much redistribution should there be, how much should we admire success of others?

But, we may never really know why our life turned out like it did. Was it because we worked hard? Or because we were lucky? It’s hard to separate these factors in our own lives. But we benefit from knowing that there’s an underlying proces that depends on both choice and chance.

Final Thoughts

For whatever reason, I felt more comfortable after I internalized this lesson. The math helped me understand it more deeply. It’s the same lesson we get from the Serenity Prayer:

“God, grant me serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

There are some things I can change, some things I can’t. Life is a random process, so let’s not worry too much.

Choice or chance?

Readers: Have your ever thought of your life as a random process? Why / why not? How much of success do you attribute to choice versus chance?