“Will you turn off that TV already?? Never!! How about in five minutes? Okay, sure.”

I can’t tell you how many times this has happened in my house. If I try to get the kids to do anything now (“Now!”), they never agree. But if ask them to do something in 5 minutes, they’ll agree to anything.

What’s happening here? I can only attribute this to My Kids’ Extremely High Discount Rates. Let’s explore…

Discount Rates

A discount rate is a term in economics that refers to how much weight we put on the future relative to the present. We value today more than we value tomorrow, and we “discount” what will happen tomorrow because it’s in the future. There’s time, uncertainty, and psychological distance between now and then, so we value it less.

In finance, discount rates are commonly evaluated on an annual basis (i.e., __% per year), and are used to discount future cash flows. In everyday life, we’re simply referring to the idea that we put more emphasis on today than tomorrow.

My kids, like many kids, have extremely high discount rates. They put so much more emphasis (like, a ridiculously greater emphasis) on the here and now instead of tomorrow, or even 5 minutes from now. One might even say that their discount rates are close to infinity (!) — that is, only the now matters.

This has a few implications for parenting.

The Marshmallow Test

The most famous example of children discounting the future is The Marshmallow Test. There are hundreds of articles on it if you search in Google and want to read more.

Here’s the basic setup: Researchers gave children the option of (1) eating one marshmallow now or (2) waiting 10-15 minutes to get two marshmallows. And, get this: they put the marshmallow right in front of the child during the 10-15 minute wait period — a true test of delayed gratification! There are some hilarious videos on YouTube of children trying to fight their desires to just eat it. Here’s one example:

Here’s the thing: Children that are able to resist eating the first marshmallow and to hold out for two marshmallows have significantly better life outcomes, decades later. They have higher test scores, higher education, higher income, a whole host of better outcomes. That is, the ability to not eat a marshmallow in preschool has predictive power on meaningful life outcomes as an adult — incredible!

The concept has been explored extensively in psychology literature and in popular publications. For example…

Self-control. Here’s a Ted Talk from my economist PhD classmate and friend, Silvia Barcellos, titled “The Marshmallow Test and Why We Want Instant Gratification.” She explains:

“As an economist studying financial and health choices, I see this all the time. People make plans for the future, that they want to follow, and that they believe are good for them, but they can’t fulfill them. So we call self-control the ability to resist the short-term temptations and follow plans that are beneficial for the future.

Silvia Barcellos, “The Marshmallow Test and Why We Want Instant Gratification,” TedxMidAtlantic 2012, at 4:15-4:45. Emphasis added.

As we grow from children to adults, we develop self-control that allows us to overcome our short-term impulses for longer-term benefit. Those of us who learn to do this better tend to be more successful in school, work, and a variety of other life outcomes.

Grit. Angela Duckworth’s Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance is all about the concept of willpower and determination. She writes:

“In sum, no matter the domain, the highly successful had a kind of ferocious determination that played out in two ways. First, these exemplars were unusually resilient and hardworking. Second, they knew in a very, very deep way what it was they wanted. They not only had determination, they had direction.

It was this combination of passion and perseverance that made high achievers special. In a word, they had grit.”

Angela Duckworth, “Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance,” Scribner, 2016. Emphasis added.

Grit is the about having the drive and vision to overcome the immediate in order to pursue the future. If we develop passion and perseverance, we can muscle through the heavy lifting that’s required in pursuing a long-term plan.

Delay of gratification. Jordan Peterson describes this eloquently (can you tell I’ve been reading 12 Rules for Life lately?):

The Delay of Gratification

“When engaging in sacrifice, our forefathers began to act out what would be considered a proposition, if it were stated in words: that something better might be attained in the future by giving up something of value in the present…”

“Prosaically, such sacrifice — work — is delay of gratification, but that’s a very mundane phrase to describe something of such profound significant… Long ago, in the dim mists of time, we began to realize that reality was structured as if it could be bargained with. We learned that behaving properly now, in the present — regulating our impulses, considering the plight of others — could bring rewards in the future, in a time and place that did not yet exist…” (pp. 164-165)

———————–

“This is to say nothing other than the future can be made better if the proper sacrifices take place in the present. No other animal has ever figured this out, and it took untold hundreds of thousands of years to do it… [it] took vast stretches of time to assess that story, to incorporate it, so that we can now simply say, “If you are disciplined and privilege the future over the present you can change the structure of reality in your favour.” (pp. 195-196)

Jordan Peterson, “12 Rules For Life,” Random House Canada, 2018, pp. 164-165, 195-196. Emphasis added.

In other words, delaying gratification — i.e., conscious discipline today to reap the benefits tomorrow — is one of the greatest evolutionary superpowers of humans relative to other animals. It allows us to organize together and harness our energy towards a bright collective future.

Back to Parenting

Okay, great. But so what? Let’s get back to parenting.

Kids don’t have the same self-control, grit, or delay of gratification as adults. So what are the takeaways? Here are two main ones:

- Near term: Harnessing high discount rates

- Longer term: Developing lower discount rates

Near Term: Harnessing High Discount Rates

Parenting is hard. Who says you shouldn’t use your adult assets, like your fully developed prefrontal cortex, to your advantage? At a minimum, let’s call it “harnessing” the high discount rates and approaching child negotiations accordingly.

Even when my kids won’t agree to comply or help now, they’ll agree to pretty much anything in the very near future:

- “Turn off that show!” “No!” “How about in five minutes?” “Okay.”

- “Go brush your teeth!” “Never!!” How about in five minutes?” “Fine.”

- “Dude, you’ve got to get started on your homework!” “I don’t even care about my stupid homework, I’m never doing it!!!” How about we get started on it in five minutes?” “Sure thing, Dad.”

Classic economic negotiation technique: Seek agreement on something that has high value to you (e.g., me: the kids completing activity X) but low value to your counter party (e.g., my kids: basically anything beyond the next few minutes).

It’s really amazing what they will agree to in the near future. Now, there can still be some resistance in following through, but my chances are much better if they’ve pre-agreed: “Hey, bud, we had agreement five minutes ago that you were going to start your homework. You know we follow through on our commitments in this family.” “Yea, okay.”

Longer Term: Developing Lower Discount Rates

Harnessing the short-term situation is all fine and well. After all, I’m usually doing it for their own long-term benefit. As a parent, I am the fully developed human brain that adequately takes into account the interests of their future selves.

But longer term, I don’t want them to maintain their high discount rates. I want them to develop self-control, grit, and delay of gratification. I want them to develop lower discount rates. Here are some ideas.

[1] Train the muscles. Developing behavioral traits is just like exercising any muscle: your kids need practice. So give them training exercises, putting rewards just out of reach relative to their current present-future evaluation. “If you take two bites of broccoli, you can have a dessert after dinner.” “If you finish your homework early, I’ll give you five extra minutes before bedtime.” Give them tangible goals that they care about and can actually aim for with improved behavior. Work the muscles so they develop strength of self-control.

[2] Set up long-term reward systems. Set up long-term reward systems that encourage your kids to think about the future impact of their present behavior. Here’s one that’s happening in our house right now: our nanny set up weekly behavior charts that result in rewards on Friday for good behavior during the week. She’s constantly reminding them that their behavior today affects the reward on Friday — that’s super helpful training.

[3] Explain short-term vs long-term trade-offs. Repeated discussion of the trade-offs also helps. When they’re making decisions for themselves, ask them to think about the short-term versus the long-term. Last night, my son spent some of his allowance on a new Thomas train. I said, “So you’re trading a little bit of your long-term savings in order to get a toy that you’re interested in, is that right?” “Ummm, yes, I guess so…” “Okay, great, let’s go for it!” “Dad, you’re a weirdo, can we just buy the toy?“ I’m not discouraging the short-term reward, but I’m trying to get him to be conscious of the trade-offs.

[4] Allow for natural consequences, in appropriate circumstances. As kids get older, natural consequences become more important. Approval from Mom or Dad only goes so far, especially for pre-teens. Lately we’ve been battling over homework completion, so I’ve been letting my son bring his homework into the teacher incomplete. But, I’ve been emphasizing the future consequences when he makes the decision: “If you don’t finish your homework now, your teacher won’t be very happy when you show up tomorrow, will she?” And then, sometimes I just let him make his own choice. The hope is that he thinks back to his short-term/long-term decision when he faces his teacher the next morning, and, hopefully, thinks about making a better decision next time.

Fun fact: Interestingly, ordering with two-day shipping from Amazon Prime seems like an incredibly high discount rate for adults: “Wow, you mean I can order anything and it will arrive in literally just two days??!” But the same timeline is actually good practice for your kids’ discount rates: “What, you mean we order it now and it won’t come for two whole days??!” Discount rates are all relative, I suppose.

We all want our children to learn to think and plan for the future. So let’s work hard to give them the skills to do so.

Final thought

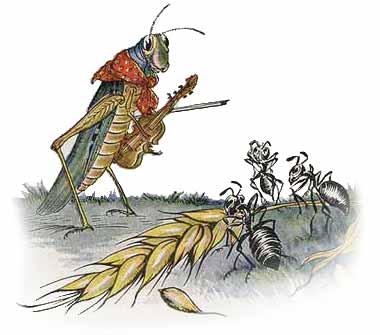

All this talk of delayed gratification reminds me of the classic story of The Ant and the Grasshopper. My wife’s great uncle John likes to bring up this story when spreading his wisdom about saving and planning ahead. It’s a fantastic children’s fable on the benefits of saving for the future. Consider telling it to your kids next time they forget to account for the future:

“One bright day in late autumn a family of Ants were bustling about in the warm sunshine, drying out the grain they had stored up during the summer, when a starving Grasshopper, his fiddle under his arm, came up and humbly begged for a bite to eat.

“What!” cried the Ants in surprise, “haven’t you stored anything away for the winter? What in the world were you doing all last summer?”

“I didn’t have time to store up any food,” whined the Grasshopper; “I was so busy making music that before I knew it the summer was gone.”

The Ants shrugged their shoulders in disgust.

“Making music, were you?” they cried. “Very well; now dance!” And they turned their backs on the Grasshopper and went on with their work.”

Source: The Aesop for Children, The Ants & The Grasshopper, http://read.gov/aesop/052.html

Let’s help out kids become ants, so they won’t be cold next winter.

Readers: Any ideas or insights in how you foster self-control, grit, and delay of gratification with your own kids? I’d love to hear about any strategies you use!

Interesting link from an astute reader:

“There’s a great recent article suggesting that we should be skeptical of the interpretation of the marshmallow test:

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/06/marshmallow-test/561779/

Super interesting! Thanks for sharing.

Here’s one of the key excerpts:

“Ultimately, the new study finds limited support for the idea that being able to delay gratification leads to better outcomes. Instead, it suggests that the capacity to hold out for a second marshmallow is shaped in large part by a child’s social and economic background—and, in turn, that that background, not the ability to delay gratification, is what’s behind kids’ long-term success.”

I’ll definitely be reading more on this! But, nevertheless, I still want my kids to try to wait for the second marshmallow. 😀