Here’s the situation: You need your child to do something important — finish her homework, clean his room, get dressed, mow the lawn, write thank-you notes, lie down for bed, whatever. You kindly ask your child to help out, and you get a strong “No” or “Not right now.” You wonder: How am I ever going to get my child to do this? And then the negotiation begins.

Hopefully negotiations with your child don’t look like this

Does the this scenario hit home? Perhaps it hits home a bit too well…!

- You: Time to brush teeth!

Child: No way. I don’t need to brush my teeth!

You: Yes, you do. It’s part of keeping healthy so your teeth don’t fall out!

Child: I don’t care if my teeth fall out…! I don’t need teeth!

You (Option 1): <curl up in fetal position on the floor>

You (Option 2): Hmmmmm… <begin negotiations>

Sometimes you just need to win these negotiations. It’s nothing personal, but kids often don’t want to do some of the basic things that they need to do to be happy, healthy, and emotionally well-adjusted. Baffling, I know, but the reality.

In these situations, I negotiate to win. I’m trying to get them to brush their teeth or complete whatever activity I need while using as little Dad capital as possible. And I use the negotiation tactics described here.

First, one comment: I get that we’re not always trying to “win” negotiations with our children. We’re not making million-dollar deals here, we’re raising well-adjusted human beings (in theory). But sometimes, if my kid isn’t self-motivated to eat a good dinner, take a bath, get to bed, or complete whatever other task is needed, it just won’t happen. So I negotiate. Because if I lose, they won’t be dressed / bathed / whatever that, in the longer run, makes me a worse parent.

For all the times when you don’t need to negotiate, feel free to disregard this advice and love your kids as much as they’ll let you. But for times when you need a win, here are some tools for your arsenal. Let’s begin!

Fair warning: This is a long post!!

Table of Contents

- Negotiating with a terrorist

- What’s a BATNA?

- Tactic #1: Know your child’s BATNA

- Tactic #2: Capturing a BATNA change

- Tactic #3: Creating a BATNA change

- Tactic #4: Know your own BATNA

- Tactic #5: Reputation is everything

- Tactic #6: Use your late-night DJ voice

- Tactic #7: Good cop / bad cop

- Final thought

- Appendix Example: Negotiating to Buy a House

1. Negotiating with a terrorist

Let’s face it, negotiating with young children or teenagers can be like negotiating with a terrorist. Consider these similarities:

- They make demands that defy basic common sense.

- They ignore your logic and reason, no matter how brilliant you are.

- They are emotional, radical, and trigger-happy.

- They have goals and objectives that you have no ability to meet.

- They have highly-specific but continuously changing preferences.

- They are willing to destroy the both of you if they have to.

- They have an endless well of time and energy to devote to the negotiation.

How do you negotiate with a terrorist? Well, just like one negotiates with everyone: figure out what each of you is trying to achieve, and find a solution that meets those needs. While it sometimes may make sense not to negotiate with terrorists — i.e., I wouldn’t recommend negotiating whether to look both ways before crossing the street — there are many instances where negotiating with your child to get a mutually agreeable outcome fosters discussion, agreement, and critical thinking.

Knowing the basic economics and emotions of negotiating will help you win the next time you need to negotiate with your child. Or at least not lose your shirt. You aren’t negotiating so that your kids “lose”. Rather, you’re negotiating for a win-win that works for everyone. The biggest wins occur when both of you have a smile on your face at the end.

2. What’s a BATNA?

The first thing you need to know is the concept of BATNA, or the Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement. In a negotiation, your BATNA defines your walk-away point — that is, what is your alternative to reaching a negotiation with your counterparty? While you both may prefer to reach an agreement, each party has an idea of how they would proceed if no agreement is reached — their best alternatives influence how strongly they are motivated to reach an agreement, and what kind of agreement range is economically beneficial for them.

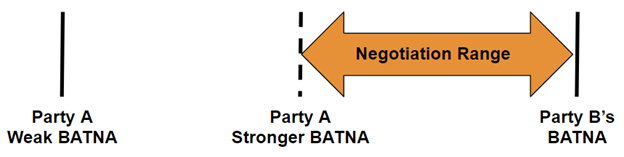

In theory, the negotiation range is anything in between the two BATNA points. If the price is lower than Party A’s BATNA, then Party A would prefer his or her best alternative to the agreement. If the price is greater than Party B’s BATNA, then Party B would prefer his or her best alternative to the agreement. Any price in between the two BATNA points represents a potential solution that is preferable to both parties’ walk-away outcomes:

A negotiation BATNA has its origins from Fisher and Ury from the early 1980s in their book, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. The authors explain:

The reason you negotiate is to produce something better than the results you can obtain without negotiating. What are those results? What is that alternative? What is your BATNA — your Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement? That is the standard against which any proposed agreement should be measured. That is the only standard that you can protect you both from accepting terms that are too unfavorable and from rejecting terms it would be in your interest to accept.

Source: Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, by Roger Fisher and William Ury, Penguin Books, New York: 1981, 1991, 2011, Chapter 6.

Successful negotiation often involves strengthening your BATNA — that is, developing a better outside option — to improve the negotiation range in your favor. In other words, you want the negotiation to look more like this:

Want to see an example? See the Appendix example on Negotiating to Buy a House.

Okay, enough theory! Let’s dig into practical applications of negotiating with your terrorist — oops, I mean your child.

3. Tactic #1: Know your child’s BATNA

Let’s translate this into negotiations with your children. The first step in successfully negotiating with your child is evaluating your child’s BATNA — what is his or her walk-away point if they don’t agree to do what I need them to do?

Here’s the situation: You need your child to do something — finish his homework, clean her room, get dressed, mow the lawn, write thank-you notes, lie down for bed, whatever. You kindly ask your child to comply, and you get a strong “No” or “Not right now.” You wonder: How am I ever going to get my child to do X? And so the negotiation begins.

You start by being more stern: If I just tell them that I *really need* them to do X, they’ll do it, right? Yeah, right. If your kids are anything like mine, that strategy works, like, once in a thousand times.

So you try to figure out what they want and what they need, and ultimately what might motivate them to complete the desired task. If you do X, I’ll read you a book. If you do X, I’ll give you a check mark / sticker / points towards a prize. If you do X, we can do Y later. Before you know it, you’re negotiating a complex corporate contract for what you’ll contribute if they do what you need them to do.

Here’s an example negotiation to try to get your child to eat a good dinner. It’s based on my own experience having one child who gets hungry after five minutes (very weak BATNA) and another child who could go for days without eating if he put his mind to it (very strong BATNA):

The Situation:

- You need your child to eat a good dinner, which is important for their growth, health, mood, and for setting a good precedent

- While you would prefer that they eat what you made for dinner (at least a little bit!), you’d rather give them some alternative food to nothing at all

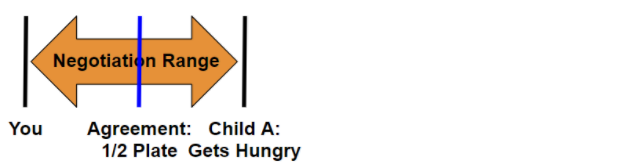

Child A: Weak BATNA

- Child gets hungry after 5 minutes

- Child cannot take strong position in negotiation what to eat

- Sample negotiation:

You: Would you mind eating your chicken and pasta, please?

Child: No — I don’t like chicken and pasta.

You: Well, that’s what’s for dinner. You need to eat it if you want dessert.

Child: I don’t care. I’m not eating it.

You: Fine, suit yourself.

** Five minutes pass **

Child: Fine, I’ll eat. How about half a plate?

You: That works for me — thank you!

You win

You win

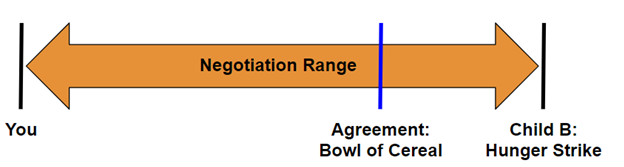

Child B: Strong BATNA

- Child willing to go on a hunger strike instead of eat his dinner

- Child can take strong position in negotiation what to eat

- Sample negotiation:

You: Would you mind eating your chicken and pasta, please?

Child: No — I don’t like chicken and pasta.

You: Well, that’s what’s for dinner. You need to eat it if you want dessert.

Child: I don’t care. I’m not eating it.

You: Fine, suit yourself.

** Five minutes pass **

You: Are you going to eat?

Child: No, I don’t like this food — it’s disgusting.

You: Well, you have to eat something.

Child: No I don’t.

You: You’ll get hungry.

Child: I don’t care.

** Five more minutes pass, though feels like an hour **

You: Fine, what do you want?

Child (silently): I win! Parents are so easy to manipulate!

Child (out loud): I’ll have a bowl of cereal. <smug look on his face>

You: Arrrrrgh, fine.

He wins

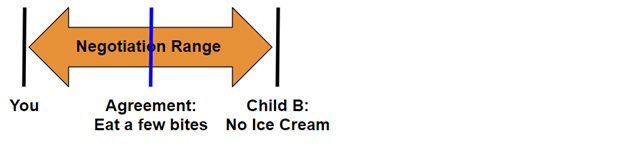

While the negotiation started similarly, Child B has a much strong BATNA than Child A. Child B is basically willing to not eat, and so he holds out for your breaking point way before Child A ever would. Because of his stronger BATNA, Child B gets a better outcome than Child A:

4. Tactic #2: Capturing a BATNA change

So what’s a parent to do? You can’t just let your Spirited Child / Selective Eater / Strong-Willed Off-Spring run (ruin?) your life, can you?

One strategy is to capture a BATNA change. You’re waiting for that little hint, that small admission or acknowledgement, that they need something, that totally changes the negotiation landscape.

Let’s go back to the negotiation with Child B. They’re holding their own for the time being. Then, all of a sudden, they blurt out something they need or want:

- You: Would you mind eating your chicken and pasta, please?

Child: No — I don’t like chicken and pasta.

You: Well, that’s what’s for dinner. You need to eat it if you want dessert.

Child: I don’t care. I’m not eating it.

You: Fine, suit yourself.

** Five minutes pass **

Child: Can I play outside after dinner?

You: AH HA!

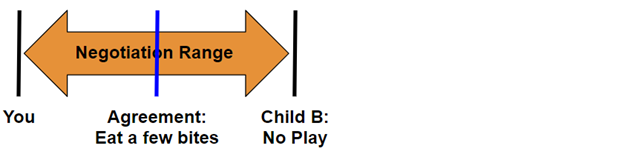

As soon as the child makes an affirmative request, the negotiation tables have turned and opportunity ensues! You are no longer negotiating over something *you want*, you are now negotiating over something *they want*. His mind, and thus his BATNA, is no longer focused on the hunger strike. It’s focused on whether or not he can play outside later. So he instantly has a BATNA that’s much closer to your desired outcome:

- You: You can play outside later if you eat a few bites of chicken and pasta.

Child: What? That’s not fair!

You: Suit yourself.

** One minute passes **

Child: Fine, I’ll take a few bites.

You (silently): Victorious! I’ve outsmarted a 5-year old!

You (out loud): Thank you, I appreciate it.

What you’ve done is you’ve changed your child’s BATNA from hunger strike to no play outside, which results in a more favorable agreement:

You’re not being cruel, you’re just using their emotions and framing of the situation, combining those with some tactical negotiations, to get a more healthy dinner. You’re channeling your child’s top-of-mind desire into other positive behaviors.

Here’s another example, based on an actual exchange at my house this morning:

- Me: Okay, kids! Time to get in the car for school!** Crickets chirp, Tumbleweed goes by **

Me: Kids — did you hear what I just said? It’s time for school. Kids?

** More crickets **

Child: Dad, can I pick out a story to listen to on the way to school?

Me (silently): Ah ha! Gotcha!

Me (out loud): Yes, of course. If you go get in the car, you can pick something out.

Successful negotiation at it best!

5. Tactic #3: Creating a BATNA change

Here’s another strategy: instead of waiting to capture a BATNA change, try to creating a BATNA change. Try this on for size:

- You: Would you mind eating your chicken and pasta, please?

Child: No — I don’t like chicken and pasta.

You: That’s fine. Although, I would remind you that we have ice cream for kids that eat a good dinner.** Long pause **

Child: How much chicken do I have to eat to get ice cream?

You: Well, well, well, Mr. Hunger Strike…

This classic parenting move — offering a reward for desired behavior (a.k.a. bribing) — will be unrecognized by only the most rookie parents. Most parents use this kind of strategy all the time.

But conceptualizing this into a BATNA / negotiation framework helps you figure out strategies to change your child’s walk-away point. If you child’s BATNA is a state that will defeat you or drive you crazy, don’t flip out or be frustrated by their position. Simply think how you might change their frame of reference as to what is at stake. Here, it’s not chicken and pasta at stake, it’s ice cream.

Here’s another example: you’re reading books to your kids before bedtime, and you know that when this book is done the conversation will devolve into “One more book!” syndrome. Once “One more book!” syndrome ensues, I almost always end up reading more, whether I want to or not.

So, what I try to do, is to get their agreement on how many books we will read before the book reading begins. In other words, get them to commit to 2 books up front, while their BATNA is weak — if they don’t agree, they don’t get any books. This is a waaaaay better strategy than trying to deal with their book requests after 1 or 2 books have been completed. Even better, stop the book in the middle, while their BATNA is that they won’t hear the rest, and get them to confirm that we’re laying down as soon as this book is done.

- Corollary: If you need your child to get dressed, brush teeth, and lie down before bed, don’t read them books before they do those things! Reading books is a joyous time for the both of you, but it’s also your best leverage to get them to take care of the other essential steps before bedtime. Instead of giving it freely, use one-on-one book time as the motivation for taking care of other chores first. Pro tip: promise them extra book time if they get ready promptly (but be willing to stick to your guns of not adding extra time if they don’t cooperate!). Second pro tip: get them to commit to turning the lights out *in the middle* of a book: “After we finish this book, we’re going to turn out the light and lay down, right?” I’ve never had a kid say no to that question if we’re in the middle of a book.

There’s nothing evil or misguided about this. After all, you’re just trying to come to a mutually acceptable agreement.

6. Tactic #4: Know your own BATNA

Up until now, we’ve been focusing on your child’s BATNA. But what about your own BATNA?

Your BATNA, or your willingness to hold firm in a situation, has a big impact on a negotiation outcome. If you’re concerned about your child’s health or mood if they don’t eat, then you’re going to give in quickly and agree to something more favorable for your child to eat. On the other hand, if you’re comfortable and confident that they’ll eat eventually, you’re more likely to hold firm and have dinner closer to your ideal outcome.

This is why your child has so much more negotiating power when you’re in a public setting. If your toddler throws a tantrum in your own home, your BATNA is pretty strong: “Go cry it out in your room, kid, and don’t come back downstairs until you’re calmed down.” Conversely, if they throw a tantrum in the middle of the supermarket, your BATNA is pretty weak, since you’ll do just about anything to reach an agreement and avoid the public embarrassment and judging: “You can have anything — candy, screen time, your sister’s lollipop — just stop the crying!”

Often, the success of my own negotiations with my kids around bedtime come down to a single factor: how busy I am with work and whether I intend to go back to work after they go to bed. If I’m feeling stressed and want to get back to my computer, my kids will sense my weak BATNA and will take advantage of me. They’ll end up getting more books (not all bad!), staying up later, and possibly even getting a snack. That kind of thing never happens when I have a strong BATNA — i.e., when I’m willing to wait out the tantrum because I don’t have a pending report to write. My amount of stress and yelling is directly proportional to the amount of work I have left to do after they go to bed. When the workload is zero, my stress and yelling are usually pretty close to zero too.

- Corollary: Try to wrap up your work before your kids’ bedtime routine. It’s better to work an extra hour earlier and be done by nighttime, then to have an hour or two of work after the kids go to bed. If you’re already mentally signed off of work for the day, your bedtime routine will be much, much improved.

7. Tactic #5: Reputation is everything

As you probably know, establishing a strong BATNA depends on your reputation for holding strong in the past. If you’ve given in quickly the previous three nights, you’re more likely to be taken advantage of the next time around. My children are like Jedi Knights when it comes to sensing my tendency to give in.

Consider this aspect of the dynamic: you’re middle-aged, you have several kids, you have a career, bills, and many demands on your time. You’ll do almost anything to reduce conflict and make sure home interactions go smoothly.

By complete contrast, your kids can pretty much devote 100% of their time and energy to getting what they want. They don’t have to log extra hours of work. They don’t have to pay the bills. They just want dessert, and they’ll do whatever it takes to get it. They’re mental terrorists, basically, with all the time in the world to undermining your position.

The key to successful negotiation with your kids is to match your actual BATNA and your communicated BATNA as closely as possible in repeated interactions.

If you say that you’re willing to give them no dessert, you better mean it. If you threaten to take away their favorite stuffed animal, you’d better follow through. Because the next time you communicate your BATNA, they’ll remember whether you held up.

You can stretch your communicated BATNA every once in a while — if you don’t clean your room, I’m going to throw out all of these toys! — but you’re generally better off if you accurately communicate your walk-away point that you’re willing to enforce.

8. Tactic #6: Use your late-night DJ voice

Even economists (really!) recognize that negotiation is more than just cold, rational calculations. Emotion and relationships matter too.

Here’s one of my favorite non-economic negotiation strategies for dealing with difficult children, from Chris Voss, author of Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depends On It. The trick is to use your “late-night DJ voice” and ask open-ended questions that get your child or terrorist (or both) to negotiate against themselves and find the best solution:

- Using the Late-Night, FM DJ Voice:

“I switched to my ‘Late-Night, FM DJ Voice: deep, soft, slow, and reassuring.”… This soothing voice was key to easing the confrontation… The best way to describe the late-night FM DJ’s voice is as the voice of calm and reason.

When we radiate warmth and acceptance, conversations just seem to flow. When we enter a room with a level of comfort and enthusiasm, we attract people toward us… Understanding that reflex and putting it into practice is critical to the success of just about every negotiating skill there is to learn. (pp. 31-32)

- Asking “How” questions:

“The trick to “How” questions is that, correctly used, they are gentle and graceful ways to say “No” and guide your counterpart to develop a better solution – your solution. A gentle How/No invites collaboration and leaves your counterpart with a feeling of having been treated with respect…

…the first and most common “No” question you’ll use is some version of “How am I supposed to do that?”… Your tone of voice is critical as this phrase can be delivered as either an accusation or a request for assistance. So pay attention to your voice.” (pp. 167-168)

Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depends On It, by Chris Voss, 2016, HarperCollins Books, New York.

In other words, put your child at ease, and let them formulate the solution. Something like this:

- You: Your room is filthy, can you clean it?

Child: I’m not cleaning. It’s my room, and I don’t have to.

You [in your late-night DJ voice]: How are we supposed to get your room clean if you won’t help clean it? <pause and stare>

** Child’s brain works and works **

Child: How about if I clean it later this afternoon?

You: Great idea! Deal.

Here, you’re using the powers of psychology and interpersonal relationships to help your child find the negotiation solution on their own. Less work, better outcome, love it!

9. Tactic #7: Good cop / bad cop

One tactic I do not recommend is the good cop / bad cop approach. That’s where one parents gets to be easy peezy and the other parent enforces the rules. “If you don’t do X, I’m going to tell your father!”

Kids are very sensitive to which parents enforce which rules. They know who’s the softy on bedtime, and who will let them eat extra dessert. Their brains map this stuff out like a detailed catalog of infinite information.

You don’t want to get into this habit where the kids “choose” who they negotiate with. Because they’ll negotiate the two of you against each other. “Dad says I could do this.” “Mom said I could do that.”

You’re way better off allowing your partner to complete the negotiation. If a kid comes to you to try to get you to be the good cop, simply say: “Well, this is your Mom’s issue” or “Your Dad is handling this” so that your partner can keep firm where they want to stay firm and give in where they want to. It’s crucial for maintaining reputation.

Good cop / bad cop might work well for criminals, who don’t have the same negotiation every day in a row. But for parents and kids, who negotiate the same things day after day, it’s a terrible strategy.

10. Final thought

Remember, we’re not trying to have *parents win* and *kids lose*. That misses the point. But practically speaking, there are times when we need our kids to do the things that they won’t otherwise do by themselves. We need strategies that produce effective behavior.

Knowing your BATNA, your child’s BATNA, and the negotiation strategies around those BATNAs provide a great starting point for persuading your child to a mutually agreeable deal.

After all, who says you shouldn’t negotiate with terrorists?

Appendix Example: Negotiating to buy a house

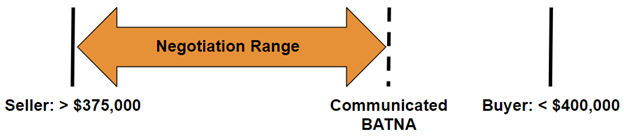

Let’s say you’re negotiating to buy a house. You tour the house and you really like it. You’re willing to pay anything below $400,000, or if the price is greater, you would prefer to go look at other houses. The seller is willing to accept anything above $375,000, or otherwise they will wait for other buyers. In other words, both you and the seller would benefit from reaching an agreement in the $375,000 to $400,000 range. Above that, and your best alternative is to look for another house. Below that, and the seller’s best alternative is to wait for another buyer. The negotiation range looks like this:

You’re willing to buy the home for $400,000 or less, and the seller is willing to sell it for $375,000 or greater. So you should be able to come to an agreement. Any point within this range is a plausible and, to some degree, acceptable outcome of the negotiation. The trick is that neither you nor the seller know each other’s BATNAs.

So your strategy is to try to communicate a strong BATNA — i.e., low willingness to pay:

- “We like the house but we have a few reservations that are holding us back.”

- “We have 3 other houses that we’re touring later today.”

- “It’s a bit of a stretch for us financially, we’re not sure if we can get a loan that large.”

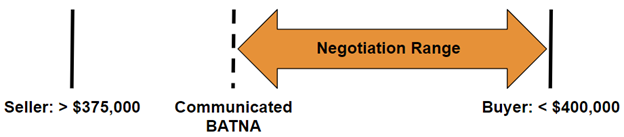

In the same vein, the seller tries to communicate that he has a strong BATNA — i.e., a willingness to accept only at a high price:

- “We’ve had 6 other families come take a look, and I’m expecting offers to come in soon.”

- “This is a high-demand neighborhood without much inventory.”

- “I’m not even sure I want to let go of this property — it’s been a great investment so far.”

In other words, you’re trying to make the negotiation range look like this:

And the seller is trying to make the negotiation range look like this:

The position of your BATNA and your ability to communicate a strong BATNA influences how good of a deal you can reach. If the other side senses that you benefit a lot from the deal or have a low outside option, they can negotiate harder over the economic surplus. If the other side senses that you have good outside options and don’t need the deal, you can usually secure a better price.

Understanding where you stand and where the negotiating party stands in terms of best alternatives is key to a good outcome.