Our family faced a big life decision recently: where to move after my wife’s medical residency. It was one of those decisions that we knew had significant impact, like whatever choice we made will shape the next decade of our lives, maybe longer.

The decision was between two job options in very different locations: California vs North Carolina. Should we go for the big city on the West Coast (the Best Coast?) or the college town on the East Coast? The decision reminded me of two things: (1) an economic story called A Tale of Two Cities, and (2) how to think about hard choices. Let’s explore…

** In actually, the decision was a bit more complex and nuanced than this, but this pair of locations illustrates some of the basic trade-offs we were facing…

A Tale of Two Cities

We all face the important question of where to live. For most of us, our original location comes from our parents. “Where are you from?”, we all get asked. Our childhood city is both deeply defining yet completely outside our control. After growing up, though, each of us decides who we want to be and where we want to live. Location becomes a key life choice.

For many of us, we can imagine living happily in different cities, each with unique appeal. City A may have great job opportunities and terrific cultural arts. City B may have amazing beauty and strong community. Cities also differ in how expensive they are.

In economic equilibrium, many cities (and neighborhoods within cities) can be appealing, because prices adjust to compensate for the existing amenities of each city. You may like living near the beach, but so does everybody else and so the homes are ungodly expensive. Alternatively, you may like the natural beauty of the countryside, and may also be able to afford it.

The mechanism behind this equilibrium is beautifully described by Steven Landsburg in his iconic book, The Armchair Economist: Economics & Everyday Life (he continues to write regularly at The Big Questions):

A Tale of Two Cities

Somewhere in the heart of the Rust Belt are two small cities: Cleanstown and Grimyville. All of the activities of daily life—shopping, working, going to the park—are equally pleasant in both cities, with one exception: breathing. The Grimyville Steel Company accounts for that. No Grimyvillian ever wakes up and fills his lungs with the crisp morning air that Cleantowners take for granted. Not only do the residents of Grimyville find breating relatively unpleasant; they also do less of it. Life expectancy is ten years lower in Grimyville than in Cleanstown.

Why would anyone live in Grimyville? For one reason: it’s cheaper. A house that rents for $10,000 a year in Cleanstown can be had for $5,000 in Grimyville. That $5,000 difference is just enough to keep folks in Grimyville. If it weren’t, people would leave Grimyville and rents would fall even further. Young people deciding where to settle are indifferent between the two towns. They like the atmosphere in Cleanstown, but they like the housing prices in Grimyville.

Stephen Landsburg, “The Armchair Economist: Economics & Everyday Life,” 1993 edition, The Free Press, Chapter 4: “The Indifference Principle: Who Cares If the Air Is Clean?”, pages 34-35. Emphasis in original.

Anyone who has ever bought a house has experienced this equilibrium firsthand. You might like Neighborhood A’s great schools and nearby park, but it’s also very expensive, whereas Neighborhood B is not quite as nice but it’s much more affordable. The key point is that prices adjust between locations so that the housing cost offsets the amenities for the marginal resident deciding between them. If one neighborhood suddenly improves (with a new school, for example), demand shifts until prices rise just enough so that the marginal resident is again indifferent.

This principle applies across cities as well (and it’s something I’ve studied quite a bit). Home prices adjust between cities to offset differences in desirability between them. On this, Landsburg writes:

Would you rather live in San Francisco or in Lincoln, Nebraska? San Francisco offers extraordinary shopping districts, world-class museums, a temperate climate, and Golden Gate Park. Lincoln offers magnificent old houses that can be had for the price of a San Francisco studio apartment. You can have the world’s finest seafood or you can have wall space…

Each year, the Places Rated Almanac and The Book of American City Rankings issue their reports on the best places to live in America. San Francisco gets credit for its cosmopolitan charm and Lincoln gets credit for the allure of its housing market…

If San Francisco is better than Lincoln, Lincolnites move to San Francisco, bids down housing prices in Lincoln, and thereby magnifies Lincoln’s relative advantages. Before long, … the two cities become equally attractive…

Steven Landsburg, “The Armchair Economist: Economics & Everyday Life,” 1993 edition, The Free Press, Chapter 4: “The Indifference Principle: Who Cares If the Air Is Clean?”, page 31. Emphasis added.

The Tale of Two Cities seemed to match our actual decision quite closely: do we choose crowded California’s endless sunshine, despite the high taxes and expensive housing, or do we choose country Carolina’s open spaces and college-town charm?

Economically, the key to answering this question is to compare your preferences to those of the marginal consumer. If you love sunshine and don’t mind crowds, then go west, young man. If you love seasons and wide open space, then stay eastbound.

Job Opportunities and Geoarbitrage

Another dimension of our choice was weighing job opportunities for my wife. Fortunately, she had great options on both ends of the country. We were grateful for her job opportunities after so many years of hard work as a medical student and resident.

An interesting economic consideration was the concept of “geoarbitrage” — i.e., geographic arbitrage — which relates to taking advantage of fundamental price differences across markets. For a primer, see these two articles from (1) Physician on FIRE and (2) Financial Samurai.

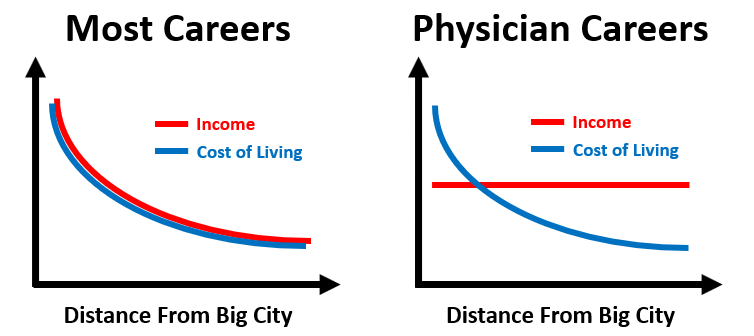

Geoarbitrage is particularly relevant for doctors since they have unusually flat incomes across geography. Most of us have job opportunities that are high correlated with population density (i.e., living near the Big City), but physician incomes are surprisingly uncorrelated:

Job satisfaction for my wife was our main priority, yet it was also worth considering the income / cost of living trade-offs in the above charts. If you’re working 40-60 hours a week as a doctor, it’s nice to feel like you’re not spending all of your income just to pay for your house. Physicians do just fine income-wise, but it’s no career in finance.

Here’s another important non-economic angle: Do you *want* to be near the center of civilization, or do you prefer a less intense existence? New York City may be a top choice for millions, but so are the suburbs and countrysides. We all find our own sweet spot in terms of living in the city, the country, or somewhere in between.

Hard Choices

Ultimately, there are so many factors to consider. How are we supposed to decide?

We were facing what philosopher Ruth Chang calls a “Hard Choice.” I’ve written about this concept before in How To Make Hard Life Choices. In her Ted Talk — incidentally, my all-time favorite Ted Talk — she uses the city versus country choice as her primary example:

What makes a choice hard is the way the alternatives relate. In an easy choice, one alternative is better than the other. In a hard choice, one alternative is better in some ways, the other alternative is better in other ways, and neither is better than the other overall.

You agonize over whether to stay in your current job in the city or uproot your life for more challenging work in the country, because staying is better in some ways, moving is better in others, and neither is better than the other overall.

Ruth Chang, Ted Talk: How To Make Hard Life Choices. Emphasis added.

The main insight is that, in hard choices, one option is not better than the other. They are different, but both are good — they are “on a par,” to use Dr. Chang’s terminology. In a hard choice, we’re not trying to figure out which option is better, we’re trying to figure out which option we stand for, and which resonates with the life we want to lead. She explains:

When we choose between options that are on a par, we can do something really rather remarkable. We can put our very selves behind an option. Here’s where I stand. Here’s who I am, I am for banking. I am for chocolate donuts…

So when we face hard choices, we shouldn’t beat our head against a wall trying to figure out which alternative is better. There is no best alternative. Instead of looking for reasons out there, we should be looking for reasons in here: Who am I to be? You might decide to be a pink sock-wearing, cereal-loving, country-living banker, and I might decide to be a black sock-wearing, urban, donut-loving artist. What we do in hard choices is very much up to each of us…

Far from being sources of agony and dread, hard choices are precious opportunities for us to celebrate what is special about the human condition, that the reasons that govern our choices as correct or incorrect sometimes run out, and it is here, in the space of hard choices, that we have the power to create reasons for ourselves to become the distinctive people that we are. And that’s why hard choices are not a curse but a godsend.

Ruth Chang, Ted Talk: How To Make Hard Life Choices. Emphasis added.

I absolutely love this concept: “Who am I to be?” “What do I stand for?” Her final words are also revealing: “And that’s why hard choices are not a curse but a godsend.” We dig deep for answers to hard choices because they tell us about who we are and the kind of life we want to live.

Our Decision

So… Who are we as a family? What do we stand for? How did we decide between California and North Carolina? Both options were appealing but for different reasons — i.e., they were “on a par” with one another. But we ultimately felt drawn to one choice over the other.

In the end, we chose North Carolina. While California had obvious allure and appeal, living in the big city there represented a more stressful and uphill climb for raising four young children. By contrast, the Research Triangle offers a highly educated community and fantastic job opportunity for my wife, but at a slower pace and smaller scale. To me, the choice represents a focus on health, happiness, and family life.

I’m hoping to stay focused on the daily timescale in our new location, hoping to slow down the speed of life while my kids grow up and define who they are and what they stand for. I think our hard choice will help make that hope a reality.

Final Thought

Certain forks in the road of life can have a huge influence on where we end up. In the words of John Lennon: “Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.” The key to hard choices isn’t figuring out which path is objectively the best, but to discover the path that feels right for each of us. I’m grateful for the latest hard choice now behind us, and for the many choices and adventures that lay ahead.

Related posts: